[Review] Empathy, Inc. is Filled with Techno-Noir Paranoia

You might not have heard of an Empathy Machine, but there’s a good chance over the last couple years you know what it is. You might have even used one. It’s a term people have used to describe Virtual Reality. In 2017, filmmaker Kathryn Bigelow premiered a VR experience called The Protectors: Walk in the Rangers’ Shoes” which allowed users to enter the shoes of a Garamba National Park ranger as they defend the park, and its elephants, from poachers and gunmen.

She described her experience with VR as profound and a way to “inform and foster empathy,” per the AP. “That’s the beauty of journalism [sic] is to bring you environments, stories, profiles of people that you otherwise have little or no access to … Here are these men and these are their thoughts. It’s very intimate and yet what they’re doing is so profound.”

She was not alone in thinking about the empathetic uses of virtual reality. In 2015, journalist Nonny de la Peña introduced “Hunger in Los Angeles,” a VR film that put people into the heart of the hunger issue and discovered that when people left the VR world, they were bawling. “I can tell you that it was the most emotional I’d ever seen people be in any of the pieces I’d worked on,” she said in an interview with Wired.

This question is at the heart of director Yedidya Gorsetman’s Empathy Inc. Written by Mark Leidner, the film is about a start-up searching for capital to create an insane version of VR, called XVR (X-treme VR, natch) that would allow its customers to inhabit a different person’s perspective in hopes of fostering empathy in the rich.

Well…sorta.

Joel (Zack Robidas) is in the midst of a crisis. Once a darling of Silicon Valley, his latest investment turned out to be built on a foundation of lies and faked data and the company needs a scapegoat. That fall guy is Joel, who was just about to close on a house with wife Jessica (Kathy Searle). Now a tech pariah in the west, he and Jessica are forced to sell everything and relocate back to the East Coast to live with her Waspy parents, Ward (Fenton Lawless) and Vickie (Charmaine Reedy). It’s awkward enough moving in with the in-laws, but these baby boomer parents come from a life of privilege, having squirreled away a million and change nest egg, and don’t understand why Joel can’t just dust off his knees and get back to it.

A chance meeting with an old friend Nicolaus (Eric Berryman) starts the gears turning when Nicolaus tells him of a new start-up called Empathy, Inc that’s looking for investors. They just need a million dollars or so to get the project off the ground. The idea behind Empathy, Inc is to let rich users experience the lives of poor people; the goal is two-fold. To put their customers’ “I had a bad day” into perspective—it can always be worse, as you know—and also to foster empathy for those less fortunate.

Joel sees potential in it, particularly after experiencing it for himself, and gets his Father-in-Law to pony up their nest egg with the understanding that they’d be able to make a ton of money with the invention. But as Joel starts to dig into the suspicious company, he starts to realize that things aren’t as they seem…in VR and in real life. And he falls down a rabbit hole of paranoia, blackouts and callousness that sends his family on a very slow burn collision course with a shadowy company hellbent on releasing their new technology.

Joel gets caught up in the implications of the XVR, mostly because Nicolaus is a shyster of the highest order. I’m fairly certain he would hawk Bigelow’s words to sell his Empathy, Inc. ideals. And who wouldn’t want to invest in such a profitable—and potentially semi-noble—cause? But those words are empty, as Joel discovers the hard way.

That’s not to say that there isn’t something to the application. After his first foray into their XVR—a process that involves drugs as well as a complicated machine—he sees a homeless woman panhandling on the street in a different light. Not only does he start giving her money, but he befriends her, calls her by her name and gives her coffee. But his second illicit XVR experience deflates the empathetic goal, as he uses his newfound freedom in VR to steal an apple in front of a police officer, attack him and then rush away. It’s a thrill for him. A no-strings or consequence way of experiencing a different world. One that doesn’t inspire empathy, but criminal freedom.

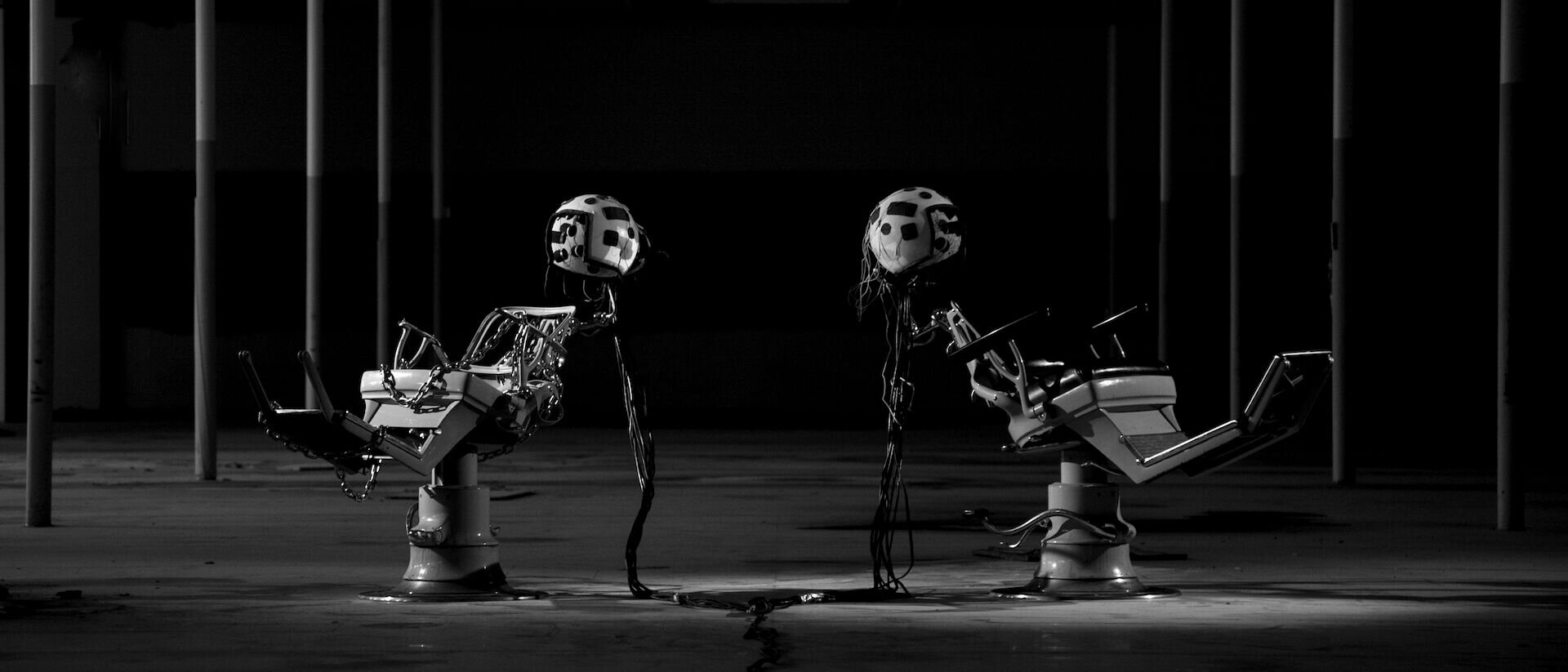

Eventually, the examinations of the propriety of this particular technology gives way to a more paranoid thriller, in the vein of the noir its drenched in. Yedidya Goresetman and cinematographer Darin Quan saturate Empathy, Inc. in black, whites and various forms of gray. The lack of color and use of shadows further establish the hardboiled, noir-inspired film. Take away the technobabble, which honestly is the least interesting part, and Joel’s investigative work could fit squarely in that conspiracy-laden and paranoia-filled era of cinema. Shady and shadowy corporations, backhanded and back alley deals abound.

Be forewarned, it’s an incredibly slow burn affair with very little action. It’s methodical and even when the action finally matches the story’s intent by the third act, it’s still a more writerly affair, filled with metaphors and themes. For example, Jessica is a stage actress auditioning for a role in an adaptation of Twelfth Night, a play about perspective-swapping and pretending to be people you’re not. It’s an slightly on-the-nose simile for the narrative, used in the same way as in some high school comedies and horror movies to further examine the themes.

What’s interesting, though, is the way it kind of subverts that expectation as Empathy, Inc. has more in common with the grand tragedies Shakespeare wrote. Cynical and nihilistic, Empathy, Inc. is a fascinating morality play that’s more about hedge funds and the callousness of the tech industry than it is the actual tech.

But back to that thought about VR inspiring empathy. Since Nonny de la Peña’s comments in 2015 , people in tech have started pushing back against the idea of VR Empathy Machines. Video game developer Robert Yang, for example, published an article lambasting the term Empathy Machine, saying that the best you could experience was an “illusion of empathy.” And, most tellingly, he said, “If you won’t believe someone’s pain unless they wrap an expensive 360 video around you, then perhaps you don’t actually care about their pain.”

I think Joel would agree.

![[Review] Empathy, Inc. is Filled with Techno-Noir Paranoia](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5b39608d75f9eef54c62c3f0/1568490624228-C2OTPT26EABHX54XHSEM/lEZA_LMQ.jpeg)

![[TIFF 2019 Review] Synchronic Continues Moorhead & Benson's Meteoric Rise](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5b39608d75f9eef54c62c3f0/1568850901246-0XQ3OGWWUSKAZ871FE0V/synchronic_0HERO.jpg)

![[FrightFest 2019 Review] Spiral is a Thrilling Tale of Paranoia and Distrust](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5b39608d75f9eef54c62c3f0/1568485694807-NOTU5USVOP305TU6AZ3W/Spiral+2.png)

![[Review] Nightmare Cinema is a blast!](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5b39608d75f9eef54c62c3f0/1561506493880-Z7JRNL3NCBQXHNLZ1SU1/MV5BNTk2NGE1YjItZWYyNS00YmJiLWJlNjgtYTJlMTQyNTg1MzZjXkEyXkFqcGdeQXVyMTI4Mjg4MjA%40._V1_SY1000_CR0%2C0%2C675%2C1000_AL_.jpg)

![[Review] Scoob! Is Scooby-Doo By Way of Marvel](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5b39608d75f9eef54c62c3f0/1589489216611-XCXAFPCT3UDZ77GHBZ7P/SCOOB_VERT_MAIN_V3_DOM_2764x4096.jpg)