[Last Call Review w/ Joe Lipsett] Episode 1 of HBO's Queer True Crime Docuseries Puts the Focus on the Victims

Each week, Terry and Joe discuss HBO’s true-crime docuseries Last Call.

Spoilers follow for Episode 1: When a dismembered body is found in New Jersey in 1992, the crime scene poses striking similarities to a murder a year prior — a case that went cold. Both victims were affluent and closeted men, last seen at a piano bar in Manhattan. The Anti-Violence Project pushes the police to investigate a potential serial killer stalking gay men in New York City.

JOE

Well Terry, we’re back on the true crime docuseries beat with HBO’s new four part miniseries, Last Call, directed and co-written by Pride’s Anthony Caronna and Howard Gertler (How to Survive a Plague).

I’ll confess right off the top that I’m something of a bad gay because I don’t know any of the details of these crimes. On the plus side, that does mean that all of the revelations within the series will be new to me. Aside from, you know, the commonplace stuff like homophobia and hate crimes leveled at the queer community, as well as police ignorance (or indifference, depending on who you ask).

Episode one kicks off in 1992 with the discovery of the dismembered body of Thomas Mulcahy; his remains left in multiple garbage bags along the highway. Mulcahy was a closeted gay man who had traveled to New York on business and was last seen having drinks at gay bar, The Townhouse, whose client is later described as “a place for older gentlemen and the young men who like them”. Lol.

When State Troopers input the details of the case into the ViCAP (violent crime database), a like minded case from the previous year comes up: Peter Anderson, a Philadelphia businessman who also frequented The Townhouse and was also later found dismembered. By the end of the episode, it’s clear that there will be at least one more victim.

Caronna and Gertler do a good job of ensuring that the murdered men aren’t simply statistics, or lurid stories for true crime fanatics to obsess over. Mulcahy’s adult daughter reminisces about missing out on conversations with her father, while Tony Hoyt, a former lover of Anderson’s, reflects on reuniting with him on the night of his murder. This helps to humanize both victims in ways that stand in stark contrast to the police testimonials that are also included in the series.

Credit to Former State Troopers like Jay Musser and Carl Harnish for agreeing to appear because neither man comes off particularly well in the docuseries. It’s clear what kind of story Caronna wants to tell with Last Call when he juxtaposes statistics about hate crimes in New York at the time (600 incidents in a 9 month period) with comments from the Troopers like “Why is the emphasis on the gay part?”

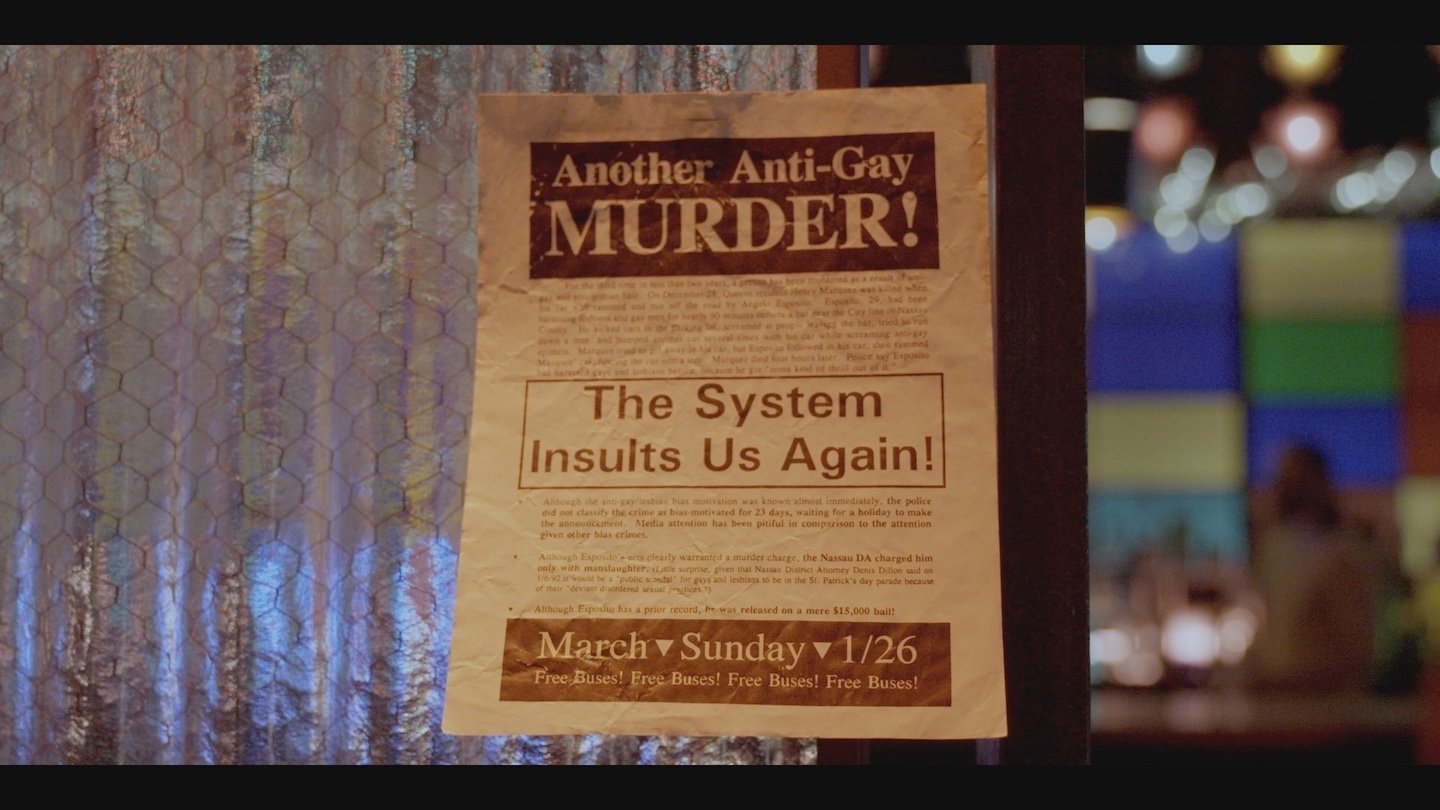

Bea Hanson and Matt Foreman, activists working at the Anti-Violence Project at the time, make a pretty obvious and compelling case linking the murders to the rise in attacks on queers within Greenwich Village and Chelsea. They associate it directly with the public’s fear of AIDS in the 80s, all of which makes the police look (as Foreman and Hanson observe) “indifferent” while their inability to see connections are either “deliberate or unconscious.”

As queer people, these statements - from the police *and* society at large - don’t feel that different from events we’re seeing in 2023. Sure, we’re not seeing men proudly declaring their hate crimes on Oprah Winfrey anymore, but the clip of one gay man exclaiming “I just want to live my life!” is legitimately haunting for anyone who has been targeted by discriminatory laws in the US these past few years.

Terry, over to you: did you also struggle with how relevant and timely the queer issues outlined in this first episode feel? Were you surprised by any of the talking head interviews, particularly the police? Had you ever heard of the term “Pick Up Crimes” before? And - without Googling - who do you think the killer is (and is it a queer person or a straight person)?

TERRY

Whew, Joe. I knew going into covering this series that it would make me emotional, but this first episode really did me in, for a number of reasons you’ve already covered. The juxtaposition of the AIDS epidemic, the paranoia and homophobia of queer people connected to the rising tide of violence really hit home. It’s hard watching this first episode a day after the SCOTUS set back gay rights by saying a person could be discriminated against because of their sexuality.

Watching Last Call, I was yet again confronted with both the fact that it hasn’t been very long since homosexuality was taken off of the mental illness list, as well as how tenuous our rights can be. The fact this first episode shows a psychiatrist wearing a mask to testify about homosexuality for fear of losing his job was frightening and confirms how real and horrible this bias was.

I think that’s the thing that Last Call does exceedingly well in this first episode. It focuses on these two heinous murders and dismemberments, but it also provides much needed context. So far, it’s doing what I want all documentaries to do: it uses a lurid crime as a hook to explore larger issues, like, in this case, police hostility/indifference, weekend homophobic bashings in the name of “fun” and the way that gay bars in the 90s were both a source of freedom and represented danger in the form of “Pick Up Crimes” and pipe bombs.

To your point, no I hadn’t heard the term “Pick Up Crimes” before, but I am aware of what they are. You don’t live in the very red Midwest and not know the fear of meeting someone and finding out they’re not who they say they are…even today.

That last part “even today” has relevance to Last Call because 1991 feels like forever ago, but the anxieties and the horrors of being a queer person still linger to this day. Shows like this are also so incredibly important because our history, at least in the last 100 years, is one of trying to find joy amidst the threat of violence and disease. Heavy thematic stuff, for sure. But absolutely necessary so we know where we’ve come from and how easy it is to lose whatever gains we’ve made.

All of this pontificating aside, Last Call manages to create a vibrant picture of the victims in this opening episode. I particularly found myself drawn to Tony Hoyt. As he was discussing his brief moments with Peter across multiple decades, you could see the forlorn look in his eyes as he reminisced about the good times.

The line that stuck with me is, “he finally had somebody he could hug…and get hugged back.”

Concerning the actual mystery, I, too, was surprised that the PA cops agreed to come on the show. You could tell they were very interested in breaking down the case, but their comments about why the director brought up the “gay part” shows how clueless the police were with the queer community.

The way the show incorporates both the Anti-Violence Project (AVP), including the AVP members who were there while this case was unfolding, and the police directly involved with the case highlights the gulf between the police and the queer community. I’m glad the police agreed to be a part of this documentary, because it does help to show the historical indifference/lack of understanding that made people in the queer community distrust the police.

As for who the killer is…I couldn’t even hazard a guess. Based on a few of the queer killers I’m aware of, it’s probably a case of deep-seated internalized homophobia.

Joe, a few moments made me incredibly emotional this episode and I’m curious if this hit you in the same way? Do you have any ideas on the killer or their motive? And did the information on the AVP surprise you–I hadn’t even heard of them, let alone the fact they had a TV show.

JOE

I hadn’t heard of the AVP, no. I wasn’t sure initially if it was related to ACT UP, but it’s not the same organization (UP was principally organized around AIDS advocacy, not supporting victims of hate crimes). If nothing else, I learned from this introductory episode about how vital community resources were when the police couldn’t be counted on for support.

I’ll confess that I didn’t feel emotional in quite the same way as you, though you’re right that Hoyt’s reflections about his generational relationship with Anderson was poignant.

Honestly, I think I maintained a certain distance from the material because of my privilege. It’s easy for me to take a (judgemental) step back because a) I’m Canadian and b) I live in Toronto, which is the Canadian equivalent of New York City.

Of course, literally moments after I wrote that, I remembered that less than a decade ago, Toronto was the hunting ground of prolific gay serial killer Bruce McArthur and the police completely ignored the calls for help from the community (Fun fact: the former chief of police during that period just ran for mayor! He lost).

So yeah, I should probably check my entitlement and stop pretending that things are that different. Queers may still have a modicum of legal protection from our government, but the reality is that that doesn’t always make the world safer for us.

One other element that is keeping me at arm’s length is how, at times, Last Call feels like something that could only happen in the past due to the lack of cell phones and the Internet. The emphasis on the physical aspects of being queer at this time - going to gay bars, congregating in queer neighborhoods - is something that older gay men of my generation (late 30s - 50s) lament is long gone in the age of Grindr, Scruff and even basic messaging apps. Would Mulcahy and Anderson have been safer if their friends or lovers could have tracked their phones or reached them more readily?

The State Troopers mention at one point that they used bank records to find out where the men were spending money and AVP had a literal hotline that had to be monitored every Monday as survivors of hate crimes reported their trauma. These are issues that are specific to a particular time period, even though the dangers they address remain relevant to our contemporary lived experience.

Aside from this, no, I don’t have any idea about the identity of the killer either. I do (sadly) agree that it is likely a closeted or sexually repressed gay man. The most infamous gay killers, like Dahmer and Cunanan (both ironically already profiled in Ryan Murphy series) harboured deep self loathing and undiagnosed mental illness, which - as you said - wasn’t helped by the public stigma towards the queer community and the lingering resentment around AIDS.

God, the 90s were a shit time to be queer.

Back to you Terry: do you think the elements of these crimes are unique to the 90s? Technically speaking, how do you feel about the way the story is being told (filmed recreations of the crime, talking head interviews, etc)? And what are your predictions for where we’ll go in the next entry of the series?

TERRY

When Last Call opened with a recreation, presumably of the serial killer leaving the spot where he dumped body parts, I cringed a bit. It reminded me of some of the problems I had when we covered Fall River. But they aren’t really relied on that much and are used mostly to keep a consistent focus on the victims, filling in moments where it would have just been a talking head.

I also think it helps that there’s more of a focus on real life footage–Oprah, the other talk show, news footage, the AVP footage, etc.–which makes the recreations more palatable. I actually like the structure of this docuseries so far, particularly as it seems to be heavily focused on the victims and showing their lives, as well as the lives and plights of queer people in the early 90s.

In the midst of writing this, I realized that this docuseries is based on a book by Elon Green and as I was going to get information for the book to share, the Amazon details page literally states who’s the killer. So consider this a warning, dear readers and Joe. If you want to follow along with the nonfiction story without knowing anything, know that there is a book and that its description lays out the central mystery.

Absolutely a lot of these crimes are somewhat more common in the 90s than they would be today, for a number of reasons. You mention the cell phone angle, which is true. So far, the victims have been closeted individuals–which was common in the early 90s, but still remains true to this day. Sure, the world is slightly more accepting to queer people (regardless of how loud the bigots can be), but closeted queer people do exist.

While it would probably be easier to track down a killer through the use of cell phones and mapping data, I do think it’s still somewhat possible that this would happen today. Maybe not to the same degree, but the homophobia, both internalized and external, and the implicit trust queer people have among other queer people are still an issue.

Instead of following someone from a bar, we’re meeting up at a random person’s house on Grindr. The modes of hooking up are different, but the results are still the same. It was sadly a lot harder to find the killer, though, in the time period Last Call is set.

Looking to the future, I’m hopeful that the next episode continues to do the work that this episode succeeded in, focusing on the victims and using the murders as a way of understanding that period of time better.

We’ll see next week when we head over to QueerHorrorMovies for episode two.

![[Last Call Review w/ Joe Lipsett] Episode 1 of HBO's Queer True Crime Docuseries Puts the Focus on the Victims](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5b39608d75f9eef54c62c3f0/1688934598503-R5X3YY9KHSO9PCHKDD36/key-art_6.jpg)

![[Review] 'Cobweb' is a Deliciously Evil Trick for Halloween Nights](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5b39608d75f9eef54c62c3f0/1689884972439-N6EUTNCABDDEIBJU5GBU/F9Fw8hKI.jpeg)

![[Exclusive Interview] The Twisted World of Twisty Troy](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5b39608d75f9eef54c62c3f0/1688403334460-WJDXP4GMQYO9ZVDBS9ZY/IMG_20230626_192353_050.jpg)

![[Lovecraft Country Review with Joe Lipsett] "Strange Case" Has a Queer Problem](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5b39608d75f9eef54c62c3f0/1600039421165-ST4871N95QOF0YI8QVUF/michael-k-williams%281%29.jpg)

![[Search Party Review w/ Joe Lipsett] Episodes 4-6 Continues the Bleak Psychological Horror Streak](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5b39608d75f9eef54c62c3f0/1611180083043-FN5B1C9B3B7LZU14R2AA/search-party_0%281%29.jpg)

![[Last Call Review w/ Joe Lipsett] Episode 4 Ends the Docuseries On a Note of Love Amongst Horror](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5b39608d75f9eef54c62c3f0/1690742918327-X8M3UODTGSSTNAWSMFUV/last-call-when-a-serial-killer-stalked-queer-new-york%281%29.jpg)