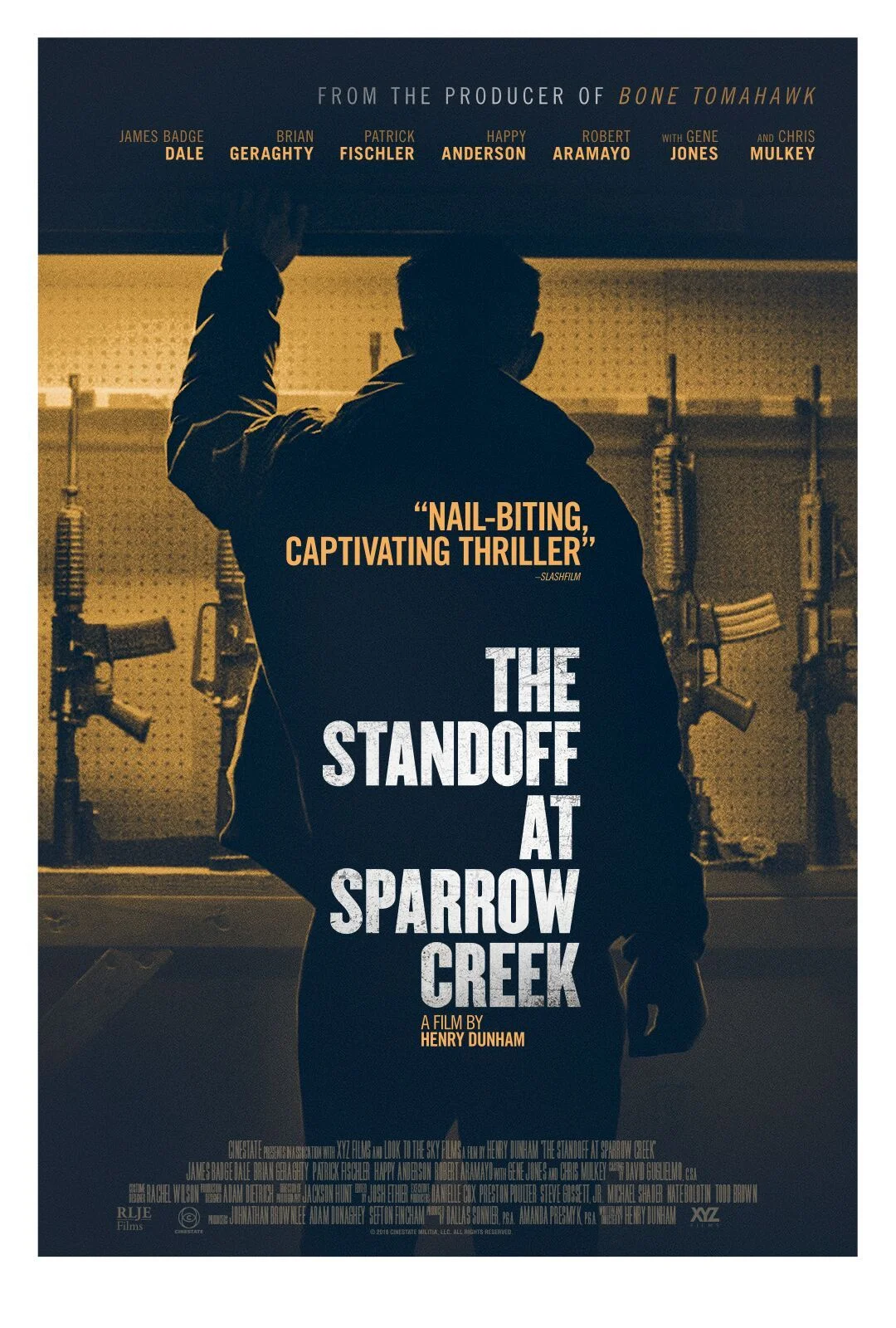

The Standoff at Sparrow Creek

I find myself in a conundrum every time I watch a Cinestate produced film. They’ve sort of fashioned themselves as a rebellious studio, operating outside of Hollywood confines. Their titles tend to be brash statements that tell you everything you need to know about the movie. Brawl in Cell Block 99. Dragged Across Concrete. The Standoff at Sparrow Creek. These are evocative titles. Unsubtle. You pretty much know what you’re going into, just reading the titles.

But the films also tend to focus on a specific kind of old school, macho masculinity. Gruff, grizzled men doing manly things. Taking matters into their own hands, even if it involves violence. Today, a lot of us would call it toxic masculinity. But I don’t think Cinestate cares what I think necessarily because I don’t seem to be their target audience. Dallas Sonnier, the owner of Cinestate, has been quoted as saying the following, in reference to a certain subsection of movie watchers they are after:

“If we can make a movie that does not treat them as losers, or ask how dare they vote a certain way, or pander to them, naturally they’re going to respond in a positive way.”

As a gay person, I find it difficult to distance this company rhetoric from a film produced by said company. It’s a sore subject, particularly for someone who comes from the middle of the country and who sometimes feels like he can’t be himself in public or at work. Someone who was deeply closeted for years because he’d been surrounded by the kinds of people who voted “a certain way.”

It’s also not helped when Henry Dunham, the writer/director of The Standoff at Sparrow Creek, tries to sidestep any discussion of the potential political messages in his film. Instead, he sees it as completely apolitical (even changing the original name from simply Militia to the new title, in order to get it made) just “helpfully” offers that he doesn’t see his characters as “alt right.” And yet, I have to admit that their creative output (outside of Puppet Master) has been uniformly excellent, even when it has questionably problematic moments and themes.

The Standoff at Sparrow Creek is no different.

It begins in the middle of rural America, with an explosion of gunfire. If you didn’t know better, you’d think you were in the middle of a war zone. A former police interrogator turned militiaman named Gannon (James Badge Dale) hears the gunfire and immediately turns on his police scanner. There’s been shots fired in public, involving police. Immediately, he goes into survival mode and he races to a warehouse with six other militiamen.

Each member comes to the warehouse with a piece of the story. Reports vary, but it seems that a man walked out of the woods and opened fire during a funeral for a cop. They say he used a modified AR-15. That he was wearing Kevlar and used explosives. They say he’s a militiaman. While all seven of the militiamen say they weren’t involved, they are the obvious targets for the police and need to have a plan. They quickly take stock of their situation: hole up in the warehouse, get rid of any evidence pointing to them and try to ride out the impending shit storm heading their way.

Except there’s a problem. One AR-15 is missing from their storage. And a Kevlar jacket. And some grenades. The killer is obviously one of them. They all have alibis; some shakier than others. So Ford (Chris Mulkey), the group’s no-nonsense leader has Gannon use his abilities as a former investigator to suss out who the guilty party is, in hopes that they can be a sacrificial lamb and save the rest of their asses. What follows is a tense wordplay between Gannon and this motley crew, who all have their own reasons for committing murder.

Complicating the ticking time bomb is the fact that Noah (Brian Geraghty), one of the militiamen, is actually an undercover cop and Ford believes his alibi is the weakest. Even though he is no longer a cop, Gannon still feels protective of Noah and makes it his duty to get a confession from one of the others in order to save him. But then the script turns the screws even further, as word starts to trickle in that militia groups are mobilizing around the country. Is this the war they’ve been preparing for?

Let’s just get to the chase. The Standoff at Sparrow Creek is an excellent film and a stupendous debut for writer/director Henry Dunham. With very little violence, he manages to create a powder keg of tension, all surrounding characters that I uniformly hated. And sure, Dunham might assert that he’s only making, “…middle American blue-collar stories without diving into anything beyond that (i.e., politics),” but the truth is far more complicated.

Take a look at our so-called protagonists. One is Morris (Happy Anderson), who belonged to the Aryan nation and has a huge chip on his shoulder towards the police. The script tries to justify that anger, to create a well-rounded character that might spark empathy, but at the end of the day the dude is a white supremacist. Then there’s Keating (Robert Aramayo), a mute young man who exhibits the kind of barely concealed, seething rage of an angrily coiled kid who is one bad day away from taking one of those legally purchased AR-15s and shooting up his school. And that’s just two of the seven militiamen, all who probably have as dark, if not darker, backstories. Try as you can to find some humanity in these characters, they are still, at the end of the day, “bad hombres.”

Then the “both sides” argument raises its head. While we barely see the cops, they are presented as part of the problem, too: uniformly corrupt and willing to do anything to rid themselves of the militias. The only insight we get is a brief flashback to Gannon’s past as an undercover officer and the kind of police corruption that ultimately led him to leave the police. There is a sort of irony in Gannon leaving one supposed pot of corruption and diving into another. But the story isn’t very interested in examining it. The focus is squarely on the members of this militia. The police become a voice on the scanner; almost a bogeyman, haunting the dark night.

As the night progresses and disinformation seems to be the word of the day, it was fascinating to see how easily and quickly these alpha men fell into delusion. How easily some people are willing to martyr themselves for some apocalyptic rationale. For me, this was the most interesting part of the movie, as it examined people with deeply held convictions and how far they'd go to manifest them, even if it meant mutually assured destruction. And I found it fascinating to watch this band of people who are only held together by some tenuous, yet strict belief system implode from distrust.

I also appreciated how assured Dunham was in creating this explosive situation and then letting his characters/actors run with it. Typical to Cinestate films, it felt a little like a 70s paranoid thriller, but seen through a more modern lens; Reservoir Dogs by way of Fincher. Utilizing dark lighting and intimate settings, the feeling of impending doom and panicked claustrophobia worked to its advantage.

As much as I didn’t care about the characters’ futures or whether they’d manage to get out of the situation alive, I still found myself unable to look away. I wanted Gannon to be able to save the undercover Noah from being offered up as a sacrifice. I wanted to know the history behind these dudes. I needed to know whodunnit.

Chalk it up to the script, yes. But also part of the fun was seeing this band of character actors chew the scenery and go to town. They act their hearts out, which is incredibly important in a movie whose tension is derived from terse conversations. From Patrick Fischler’s weaselly computer nerd, running information from the police scanner to the militiamen to Chris Mulkey as the boss, these are actors who will make you run to IMDb because you know you’ve seen them somewhere. And they all are uniformly excellent.

So I guess that’s the greatest compliment, right? That I can be so conflicted about the story, both inside and outside the film’s narrative, and still enjoy the hell out of it. I think that’s the key to Cinestate’s success. Hire directors with uncompromising voices and give them carte blanche to create the movie they want. It’s worked so far and I think The Standoff at Sparrow Creek is the studios best work yet.

![[Review] Horror Noire: A History of Black Horror](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5b39608d75f9eef54c62c3f0/1549054482540-F19QHCSZ9FU8GR8HXJJH/horror-noire.jpg)

![[Review] Happy Death Day 2U](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5b39608d75f9eef54c62c3f0/1550112111784-I3VKZ6BSKCCJGTFXVY8P/MV5BMTg0NzkwMzQyMV5BMl5BanBnXkFtZTgwNDcxMTMyNzM%40._V1_.jpg)

![[Review] Pet Sematary (2019)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5b39608d75f9eef54c62c3f0/1554421493371-P0JRMX3657TZ033U890D/MV5BMjUyNjg1ODIwMl5BMl5BanBnXkFtZTgwNjMyOTYzNzM%40._V1_.jpg)